Scrolling through Instagram, I stumbled upon a video of Stephen Hawking doing stunts in his wheelchair, spinning, racing, wrestling, defying gravity. For a fleeting moment, I believed it was real, until I remembered that Hawking is dead. Then came a dog firing a gun, a squirrel slurping spicy ramen, a woman morphing into a lizard-like creature in the middle of a busy street, and a bunch of rabbits bouncing joyfully on a trampoline. For a second, I almost believed all of it. My feed had turned into a surreal theatre of algorithmic imagination, invoking equally absurd, hilarious, and slightly unsettling emotions. Amidst this doomscrolling, there was a sudden realisation that these AI-generated clips don’t just play with our sense of humour or wonder, they alter our idea of what’s real, teaching us to doubt our own eyes in ways that feel deeply disorienting.

But it also makes me wonder how long this harmless fun can stay before it starts to warp our sense of reality, and before the joke begins to shape how we see the world and each other. And more importantly, beyond the screen, there’s the cost of massive energy and water consumption powering this bizarre amusement and “technological innovation” that we don’t see. So I question if this moment of entertainment is really worth the environmental toll we’re leaving for the generations who’ll inherit what’s left of our planet?

Historically, every economic revolution was popularised at the expense of those who benefitted from it the least. The Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages was praised as a breakthrough in global trade networks, but it depended crucially on enslaved labour, the dispossession of indigenous lands, and resource plunder across Asia, Africa, and the Americas. This revolution was dependent on the motives of expanding colonisation in the name of trade and exploration, and laid the foundation of the Industrial Revolution.

The industrial revolution, similarly, was framed as progress via steam engines, factories, and mechanisation, but it was built on colonial extraction of raw materials like cotton, jute and tea, from the communities, as well as labour under coercive colonial rule, and ecological damage in territories far from the factories. Labour historian Anna Sailer’s book, Workplace Relations in Colonial Bengal, documents how factory management reshaped labour practices, changed shift systems, and disrupted local rhythms of life, turning entire communities into extensions of industrial output for imperial profit rather than sites of self-determined economic life.

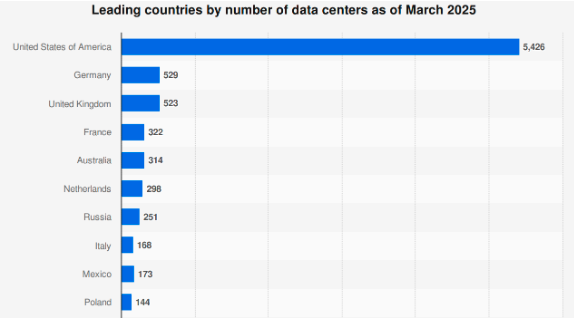

These histories may seem like distant relics, but they in fact resonate in the current tech revolution. AI, like industrial machinery, rests on extraction of resources like precious minerals, rare earths, water; digital labour including data annotation, content moderation, crowdsourcing; and energy-hungry infrastructure like data centres, generators, and cooling systems. Just as British textile mills depended on Bengali weavers during the industrial revolution, today’s AI models depend on underpaid and overburdened work from annotators largely located in the Global South.

Today, while the global North shapes the narrative around AI as innovation, progress, prosperity, and inevitability, the global South lives its costs

As Nanjala Nyabola points out in her book, Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics: How the Internet Era is Transforming Kenya, digital colonialism emerges when infrastructure, data storage, governance, and value flow align with colonial patterns, even when the surface discourse is about connectivity, innovation, or inclusion. By these standards, AI systems are not neutral machines, instead they mirror the colonial map highlighting centres and peripheries determined by money, power, and historical extraction, not by human need or justice.

Today, while the global North shapes the narrative around AI as innovation, progress, prosperity, and inevitability, the global South lives its costs. AI systems are not immaterial, and in fact depend on extractive infrastructures, including vast networks of data centres, undersea cables, and gig workers, that consume energy, water, and human effort at an unprecedented scale. Zoya Rehman, a researcher with experience in digital rights and climate change advocacy from Islamabad, argues, “digital colonialism isn’t a metaphor. Tech companies rely on super concrete forms of extraction from the South.”

However, as the world celebrates breakthroughs and innovation in generative AI while technology companies boost profits, very few stop to ask whose land, labour, and data keep these machines running, or who is paying the ecological price for someone else’s technological dream.

A Business Insider investigation revealed how Big Tech’s race to dominate the AI industry is reshaping entire local environments in the United States. Corporations like Google, Amazon, and Meta are pouring billions into building vast data centres to meet the world’s AI demand, often in small towns that are promised jobs and development in exchange for generous tax breaks. But the reality is far from equitable as these centres are frequently built beside residential areas, where they consume large amounts of electricity and fresh water to keep their servers running. The millions of gallons of same water that sustains local communities is being diverted to cool machines, leaving residents to face water shortages and rising utility costs.

Source: Statista via World Economic Forum

But beyond these towns in the US, the damage is also global. The materiality of AI, i.e. the servers built on cobalt mined in Congo, or the datasets annotated by Kenyan or Indian youth for less than $2 an hour, reveals the power imbalance between those who build and profit off of technology and those who sustain it.

Rehman says that the labour is fragmented into tasks that are deliberately kept invisible, so [the workers] cannot organise easily or claim authorship. The platform economy pushes them into precarious, individualised work arrangements where income, time, even health are sacrificed for a fluctuating algorithmic wage.”

In addition, the immense heat emissions from data centres accelerate carbon buildup, intensifying the very climate crisis that disproportionately impacts the world’s poorest and most vulnerable communities.

Sana R Gondal, an urban and environmental planner from Pakistan, points out that AI data centres often depend on backup generators powered by fossil fuels. This reliance, she explains, significantly amplifies their carbon footprint, intensifying the very climate crisis that the technology industry claims to be innovating its way out of. “The heat generated ends up affecting already climate vulnerable spaces.”

In the name of progress, it is a quiet form of environmental extraction, where the planet’s resources are exchanged for the illusion of technological advancement.

“What looks like ‘innovation’ in the West especially translates into intensified extraction, debt, and climate vulnerability in the global South,” Rehman says, further explaining that, “countries like Pakistan are then pressured to provide cheap energy and tax holidays to attract data infrastructure in the name of growth, while shouldering the environmental degradation and long-term water stress.”

Pakistan is among the 10 worst affected countries by climate crisis, facing increasing climate disasters, deepening energy crises, and the quiet proliferation of digital colonisation.

She sees a political feedback loop in this process. When digital infrastructures are controlled by foreign corporations, states in the global South are tempted to trade regulatory concessions for investment. “That weakens labour protections, environmental safeguards, and data rights at precisely the moment when stronger climate governance is needed. For Pakistan and other climate-vulnerable states, digital colonialism therefore greatly intensifies both economic dependency and ecological risk.”

Impact of AI innovation in Pakistan

Pakistan is among the 10 worst affected countries by climate crisis, facing increasing climate disasters, deepening energy crises, and the quiet proliferation of digital colonisation.

Much is yet to be understood and explored about how Pakistan’s land, resources and labour are being drawn into the global AI revolution. But its impact is already visible, and deeply felt by communities on the ground. A 2025 Climate Risk Index found that Pakistan was the most affected by the climate crisis in 2022 alone with loss of lives (at least 1700 fatalities reported), significant internal displacement (over 8,168,000 people), as well as a direct impact to its economy that cost the country over 15 billion USD along with an estimated 16 billion USD for reconstruction.

Urban centres are reeling from record-breaking floods year after year, while semi-urban and peripheral regions are disappearing under melting glaciers. With harsher weather, electricity grids collapsing every summer, and floods becoming an annual occurrence, the environmental burden of these infrastructures feels especially cruel for those least responsible.

So it begs the question – does Pakistan contribute to the climate crisis anywhere near as much as it suffers from it? The data says no.

In 2023, Pakistan accounted for just 0.5% of global carbon emissions. Compare that with China’s 31.5%, the United States’ 13%, and India’s 8%, and the disparity becomes evident. Pakistan’s emissions barely register on the global scale, yet its people are paying the highest price.

In 2023, Pakistan accounted for just 0.5% of global carbon emissions. Compare that with China’s 31.5%, the United States’ 13%, and India’s 8%, and the disparity becomes evident

Gondal says, “Pakistan, with its largest concentration of glaciers in the world, is a lot more climate vulnerable than the US, which is the largest polluter and carbon emitter in the world.” This imbalance is also a reflection of climate injustice built on the same extractive logics that once powered colonial empires.

Is Pakistan prepared?

Pakistan has established several core legislative and regulatory instruments to address climate change, prominent among them is the National Climate Change Policy (NCCP) 2012. It sets out adaptation and mitigation goals across water, agriculture, forestry, coastal zones and vulnerable ecosystems, and updates every five years in collaboration with UNDP. In addition, the government’s National Adaptation Plan (NAP) 2023 builds further by articulating institutional arrangements, financing strategies, and gender-sensitive priorities for climate resilience. The Plan addresses the “social inclusion” of various communities, including women and youth, and states: “Unequal participation in decision-making processes across all sectors and domains perpetuates and exacerbates inequalities for vulnerable groups. This disparity hinders their ability to fully contribute to climate related planning, policymaking, and implementation, despite possessing valuable knowledge and capabilities. The lack of representation and involvement of these groups in crucial climate-related discussions not only limits the diversity of perspectives but also overlooks the unique insights and experiences of the indigenous community.”

Rehman resonates with this framework and says, “when it comes to core decisions on energy policy, water governance, land use, public finance, the space is still dominated by male bureaucrats, engineers, and overall political elites.” She says that part of the reason for this exclusion is because the climate policy is still framed as a technical and security matter rather than a social and political one. “That framing privileges certain male-dominated professions and sidelines feminist and grassroots knowledge.”

She further says that patriarchal norms within ministries, parties, and professional networks also limit women’s full ability to exercise agency fully in decision-making roles, particularly women from working-class, rural, generally peripheral communities. “Without women’s organised power at the table, climate action tends to reproduce existing hierarchies: land remains in the hands of large owners, energy decisions privilege industry over households, and as we can see, adaptation funds move through the same patronage networks that have always excluded non-privileged women.”

For all its climate strategies and frameworks, Pakistan continues to face a “significant gap between the formulation of climate policies and their effective implementation.” A study notes that although the Pakistan NCCP and related frameworks set out roles for provincial bodies and institutional coordination, in practice these structures “have rarely convened or delivered concrete plans” across provinces exposed to high risk.

More specifically, research on adaptation policy implementation identifies major barriers like top-down management, weak stakeholder inclusion, and “misinterpretation, poor understanding amongst policy implementers and false expectations of policy goals.”

So even though Pakistan’s policy framework appears robust on paper, Madiha Latif, Vice President Strategic Engagement and Innovation at Pathfinder, says, “weak governance structure and poor implementation of otherwise robust policy frameworks, limited human and capital resources coupled with outdated tech are some of the issues and barriers.”

Technological and economic growth, but at what cost?

A rights-based framework insists that the burden of climate and technological change be measured in fundamental rights, not corporate opportunities. Pakistan’s decision to allocate 2,000 megawatts of electricity to bitcoin mining and AI data-centres, for instance, may appear as a development strategy, but through a feminist lens it raises urgent questions of equity and justice. When digital infrastructure competes for scarce resources like energy, water or land in a country already ranked among the most climate-vulnerable globally, the rights to life, health, clean water and decent work for marginalised communities are significantly undermined. It is telling that not only corporations that centre their economic interests in every decision they make, but the government that serves the people of the country is also geared by financial growth, over the well-being and sustainable futures for the people.

“From security to nutrition, education, and overall quality of life,” Gondal says, “women and gender-diverse people are always impacted far more deeply.”

Most studies on the impact of climate change on vulnerable populations focus on losses in terms of fatalities, economic costs, displaced households, but rarely ask who those numbers belong to. Behind every statistic are people who did little to cause the crisis they are now forced to survive. The floods, heatwaves, and droughts are not just natural disasters, instead they are lived disruptions that reorder entire ways of life. And while climate emergencies may appear indiscriminate, their consequences are more severe on women, gender-diverse people, and other intersectionally marginalised communities who bear the heaviest burdens. When extractive digital infrastructures and intensifying climate hazards merge, it is these groups who lose the most, be it livelihoods, homes, access, and agency, all while being left out of the decisions shaping their future.

“From security to nutrition, education, and overall quality of life,” Gondal says, “women and gender-diverse people are always impacted far more deeply.” She explains, “their needs are more specific, like access to hospitals, proper nutrition, and safe shelter, but during disasters like floods, these become inaccessible. They are often forced to leave their homes, separated from family or community networks that protect them, which exposes them to greater danger.”

She adds, “in temporary shelters, even something as basic as access to a bathroom becomes unsafe, leaving them vulnerable to harassment, assault, or abduction. And when disasters hit, one of the first things to go is a girl’s education, limiting her ability to grow into adulthood before being married with any real agency.”

Latif agrees, “they are also more likely to be pushed into poverty and face greater food insecurity compared to men and boys.” Owing to Pakistan family and societal structures, she says that women are also forced into the roles of caretakers in times of climate crisis. “It leaves women more physically, emotionally, and mentally burdened.” She also says that women face greater trauma post crisis as well in the form of sexual exploitation and violence in camps, making them more vulnerable.

A rights-respecting policy in Pakistan would demand that technology infrastructure developments are subject to participatory review, impact assessment and social licence from affected communities, not simply top-down investment decisions. Only by situating digital governance in collective rights and redress can Pakistan counter the dual extraction of its climate and human resources in the name of innovation.

Business responsibilities

Nearly every major tech corporation has pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2030, yet their rapid expansion of massive data centres around the world tells a different story. These infrastructures demand tremendous amounts of energy and water, forcing entire regions into extractive cycles of resource depletion. As a result, climate-efficient initiatives and fancy sustainability campaigns cannot offset the emissions and environmental damage these corporations continue to produce, certainly not at the scale at which they operate.

So the responsibility for protecting and preserving the planet’s liveability must lie most heavily on the very businesses driving its degradation, as they are the principal architects of the climate crisis experienced in countries like Pakistan

Many corporations continue to externalise environmental risk, offshoring heavy emissions, exploiting vulnerable labour, and situating extractive operations in jurisdictions where governance is weak. Legal commentary has observed that the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) apply to “environmental harm” when business activities contribute to human-rights impacts, even if corporations themselves do not directly cause those harms. So the model of global tech firms locating digital infrastructure, resource-intensive data farms or labour-intensive annotation centres in an environmental situation that poses existential risks to communities and entire countries becomes all the more problematic.

However, the global regulatory framework for AI remains weak, shaped more by corporate lobbying than by public interest. Tech giants like OpenAI, Google, and Meta are spending millions to influence governments to dismantle regulatory barriers in the name of innovation. Governments in the global North, especially the United States, have been receptive as the Trump administration’s AI Action Plan, for instance, makes clear that the US has no intention of regulating AI with the same rigor as Europe. However, even within the EU, despite the passage of a relatively robust AI Act, several member states are already softening their stance to attract AI investment. As a result, the governance landscape is designed around capital, and not accountability.

It is worth noting that under international norms, businesses cannot simply claim innovation as a shield, and it must be balanced with the rights of local populations to resources like water, clean air, safe housing and dignity. Failure to do so undermines their legitimacy, while violating global expectations, and deepening human and environmental vulnerability.

So the responsibility for protecting and preserving the planet’s liveability must lie most heavily on the very businesses driving its degradation, as they are the principal architects of the climate crisis experienced in countries like Pakistan. Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), companies have an independent responsibility to “avoid infringing the human rights of others and to address adverse human-rights impacts with which they are involved.” This means that even when local laws are weak or non-enforced, the corporate duty to respect human rights remains.

Meanwhile, the UN Global Compact, through its Ten Principles, explicitly links business conduct to environmental accountability. Principle 7 of the Compact urges companies to take a “precautionary approach to environmental challenges,” Principle 8 asks them to “undertake initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility,” and Principle 9 commits them to “encourage the development and diffusion of environmentally friendly technologies.” In practice, these frameworks demand far more than green-washing, and call for business models founded in justice, resource stewardship, and the recognition that the right to a safe, healthy environment cannot be outsourced to the margins of global value chains.

However, these principles are rarely seen in corporate practice, as the gap between ambitious commitments and entrenched business models is staggering.

Rehman says that accountability cannot be left to voluntary commitments or fancy sustainability reports. She suggests, “binding emissions caps, strict disclosure of full lifecycle emissions – including supply chains and downstream use, an end to weak offsets, and substantial taxes on excessive energy use that can be channelled into climate loss and damage funds, as some of the strategies that global North governments should prioritise as strategies for accountability.”

She further suggests concrete global strategies for accountability that prioritise transparency, emphasising the need to hold corporations responsible for contributing to climate emergencies, and not just technological innovation. She says, “international human rights and climate mechanisms must treat digital corporations as subjects of climate responsibility, not as mere “stakeholders”. That includes integrating tech sector scrutiny into the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process, the UNGPs, and climate loss and damage negotiations. Regional bodies and coalitions of global South states can also coordinate to demand climate and labour due diligence from tech companies as a condition for market access.”

Rehman concludes that “net-zero will remain PR vocabulary while emissions and extraction continue” unless actionable and intentional steps are taken towards mitigation that “pressure companies in ways that formal diplomacy just cannot.”